Derek Humphry is considered by many to be a founder of the death with dignity movement in the United States. Since founding the pioneering right-to-die organization The Hemlock Society in 1980, Humphry has been a leading advocate for the right of terminally ill individuals around the world to decide how they die.

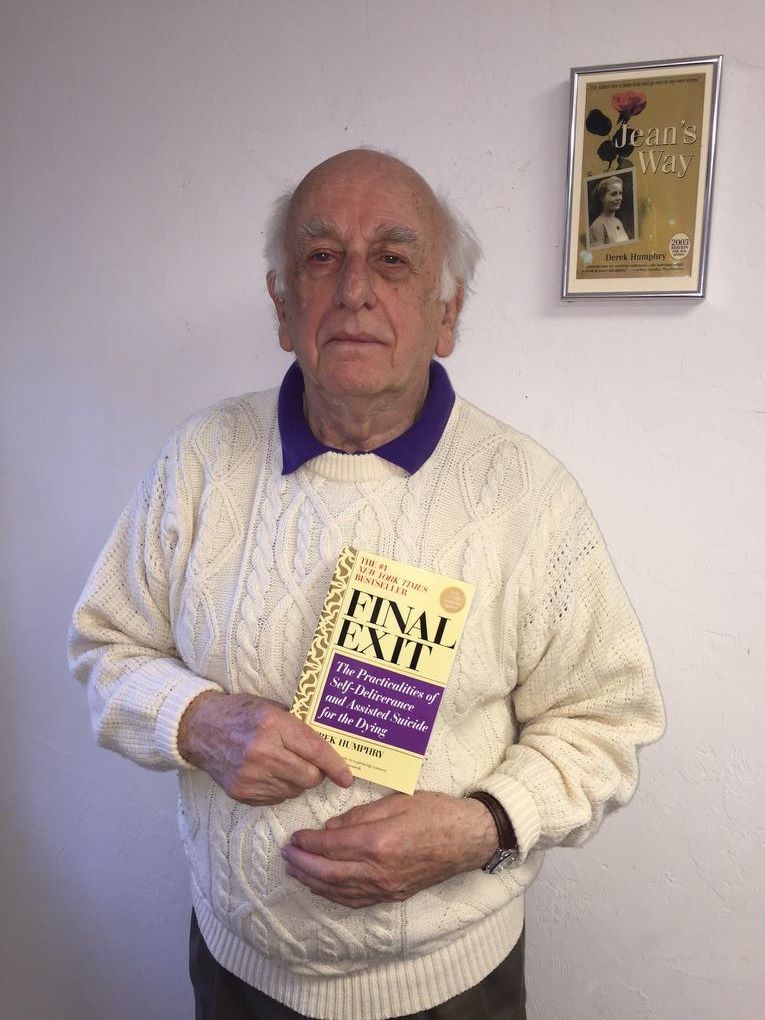

In 1991, Humphry’s book, Final Exit, topped U.S. bestseller lists and immediately ignited controversy. Characterized by many as a “suicide manual” but described by Humphry as “the thinking person’s bible to self-deliverance and assisted dying,” the book catalyzed a nationwide conversation about death with dignity as an end-of-life option.

Humphry was involved in early ballot-initiative campaigns for death with dignity laws in Washington and California, and his contributions to the 1993-94 campaign to pass legislation in Oregon helped it succeed.

He has long been recognized as a high-profile advocate for the legalization of medical aid in dying – and, more controversially, euthanasia – worldwide, and for decades was a sought-after speaker at conferences and legislative hearings. In 2014, the World Federation of Right to Die Societies honored Humphry with its Lifetime Achievement Award “for contributing so much, so long, so tirelessly, and so courageously to our right to a peaceful death.”

Now, Humphry, who turned 90 in April 2020, spends less time traveling and more time at his home in Junction City, Oregon. In this 2019 interview, edited for length and clarity, Humphry reflects on his personal journey from grieving spouse to bestselling author and, eventually, a leader in the movement for self-determination and freedom from suffering at the end of life.

*

Humphry’s life’s work is informed by a deeply personal experience. In 1974, his wife, Jean, was dying of breast cancer that metastasized and spread to her bones. She had done multiple rounds of chemotherapy and many hospital stays over more than two years.

One day she said to me, “I don’t want to be in hospital. When I’ve had enough, I want to then die when I can’t take the pain.”

At the time, the right-to-die movement was very small. There was no publicity around it. I’m not sure I even knew the meaning of the word euthanasia. So I said, what do you want me to do?

She told me, “Go to the doctor, get an overdose of drugs which will end my life immediately. I’m not ready to go now, but I know it’s going to be in a short while. I want you to promise me to do this.”

I said I would help her.

Court Cases on Assisted Dying

I worked for the Times of London as a journalist. I had access to their library going back a long way. I looked at the files on assisted suicide, and I was struck very forcefully by the fact that a fair number of people over the years had been brought before the courts and charged with assisting their spouse’s suicide, but while they were found guilty, they were never sent to prison. The judge would say, you’ve been breaking the law, but I’m going to put you on probation. You could tell the judges didn’t feel that this was an incarceration offense. That shocked me.

“A Chance I Can Take”

I looked up the law in the local law book and it said prosecutions for assisted suicide can only be taken by the director of public prosecution. He or she controls all prosecutions in Britain for serious offenses. I knew the public prosecutor in London, from my reporting on civil liberties and immigration matters I knew he was a very compassionate, sensible man. I thought, this is a chance I can take.

A Secret Promise

I knew a doctor personally in London through my journalism work. And I went to him and I said look, Jean wants to take her life in the near future. He interrogated me about Jean: what her situation was, what her treatments were, her level of pain. He said, she has no quality of life left, of course I’ll give you the drugs in secret. You must never tell anybody I did this for you. We shook hands and I promised I would never reveal his name.

He gave me the two medications and I took them away, hid them in the house. I told Jean, I’ve got these medications, they’re hidden away for when you ask me. She wasn’t anxious to die; she even did a third round of chemotherapy. On the other hand, she knew she did want to die at a certain point, when the pain became too much to bear.

“I’d Like to Die Today”

Four months went by until March 1975. The bone cancer was terribly painful for Jean. The hospital said, well, she can die in the hospital, or you can look after her at home. We went home. After a few days, when it got worse and worse, she said, “I’d like to die today. Do you agree?”

She’d asked me not to sanction her suicide if it was not the right time. I talked to the doctors privately and they said, she’s going to die. There was nothing else they could do for her.

She was a woman of her own mind. She respected doctors, but she didn’t think they controlled her life entirely. She said to me, “I’d like to die at 1 o’clock today.” I paused for a moment, then said, yes, I will help you.

The Final Hours

We spent the morning together talking, laughing, crying, playing her favorite music. She gave me permission to marry again whenever I wanted. We had three sons, they were teenagers; she said she told them they needed to respect my choices.

When we got to 1 o’clock, she said, go and get it. I went and got the medications, mixed them in a cup of coffee, put some sugar in it to try and drown out the bitterness. I told the boys that she was preparing to die. She had called them in the previous morning to say goodbye. She told her girlfriends. Amongst confidential people she let it be known.

I took the coffee to her. I said, if you drink that, you will die. She understood.

We had a last hug and a kiss. I helped her to pick up the coffee and drink it. She picked it up, gulped it down, and said, goodbye my love. Very quickly she went unconscious, and died 15 minutes later.

Writing Jean’s Story

I was staggered at her courage. In the back of my mind, I knew I wanted to write an article about it later. I decided to write a little book about it to tell a story. I waited a year after Jean died to write an article; I needed to give myself some distance. But I couldn’t get anybody to publish it at first.

When a paper finally published the story, the response from readers was tremendous. The editor told me the paper had never received so many letters about a story.

In 1976, my first book, Jean’s Way: A Love Story, was published as a hardback. It sold out its first print run in a week.

Defending A Decision

I did a lot of radio and television interviews, and found myself having to defend what I did. The law, the morality, the ethics of this really sparked conversation.

I went to Australia and New Zealand to speak about it. I got to America and had more speaking inquiries coming in every day.

A New Life in America

I joined the L.A. Times as a journalist in 1979. My second wife, Ann, was American, so I got instant acceptance.

In addition to my journalism work, I found myself wondering what I wanted to do with the campaign I’d started after Jean’s death.

Founding the Hemlock Society

So, with Ann, I founded an organization in 1980. I chose the name The Hemlock Society, a reference to the lethal plant Socrates used to end his life. It seemed like a fitting name.

We announced the founding from the Los Angeles Press Club.

Some people were skeptical of our campaign and the concept, but people began to join.

And what they wanted was an answer to the question, how do I kill myself when I am terminally ill?

The Society Grows

I told them, I’ll write you a guidebook on how to do it. So I wrote a little guidebook, called it Let Me Die Before I Wake, and sold it to Hemlock members. It sold very well. After that, The Hemlock Society began to grow. By the end of the decade, Hemlock would have over 50,000 members.

Campaigning in California

I turned my attention to passing a law that would legalize the practice [of assisted dying]. When I would speak with legislators in California, they would say, well what law do you propose, Derek? I got together a committee of pro bono lawyers who were interested in the subject, and a professor of law. Every Saturday, we would sit down at one of our houses and we worked to draft a law.

The First Model Law

I was the common-sense person in it. I asked questions like, will the public understand this kind of thing? We drew up the Humane and Dignified Death Act, the first such model law in America. We put it on a ballot initiative in California and Washington [in the late 1980s and early 1990s] and lost both times. We didn’t have a big enough organization, or funding, or experience at that time.

Moving to Oregon

In 1988, I decided to leave L.A. and take Hemlock with me. I picked Eugene, Oregon as a new home, so I moved Hemlock to Eugene and founded the Hemlock Society of Oregon. Hemlock grew and attracted doctors, lawyers, and nurses in Portland, who became members.

They argued that because Oregon’s initiative system was the first of its kind in the nation, it was not as hard to place an initiative on the ballot because there was a greater degree of familiarity with the process. Moreover, advertising in Oregon was substantially less expensive than it was in California, meaning we could get a greater degree of exposure for an initiative in the media.

To the Legislature

I still decided to take the draft law to the Legislature. Fortunately, Oregon State Senator Frank Roberts supported us. He was the first legislator in America to introduce our version of the Death with Dignity Act.

When I went up to [the Oregon State Capitol in] Salem to speak about the legislation at a hearing, I took a colleague or two [from Hemlock] with me. We were laughed out of the house. Nearly all of the audience had black gowns on [to symbolize death]. We were drowned out by the opposition.

We [Hemlock] got nowhere with the Legislature, but we got attention. It was only the beginning.

*

Final Exit

In 1991, Humphry published Final Exit, a how-to book on self-deliverance. Within 18 months the book sells 540,000 copies and tops USA bestseller lists. It is translated into twelve other languages. Total sales exceed one million. The book catalyzed a nationwide conversation about death with dignity as an end-of-life option.

I didn’t know Final Exit would have the massive impact it did, but I did know it would be controversial.

To this day it still sells a good number of copies per week. I’m planning to release a new, updated version in 2020 that covers the growth of the assisted-dying movement.

*

Oregon Right to Die

Those of us working to pass a law in Oregon knew our only path was through a ballot initiative. The Hemlock Society was a nonprofit; we couldn’t run a ballot-initiative campaign.

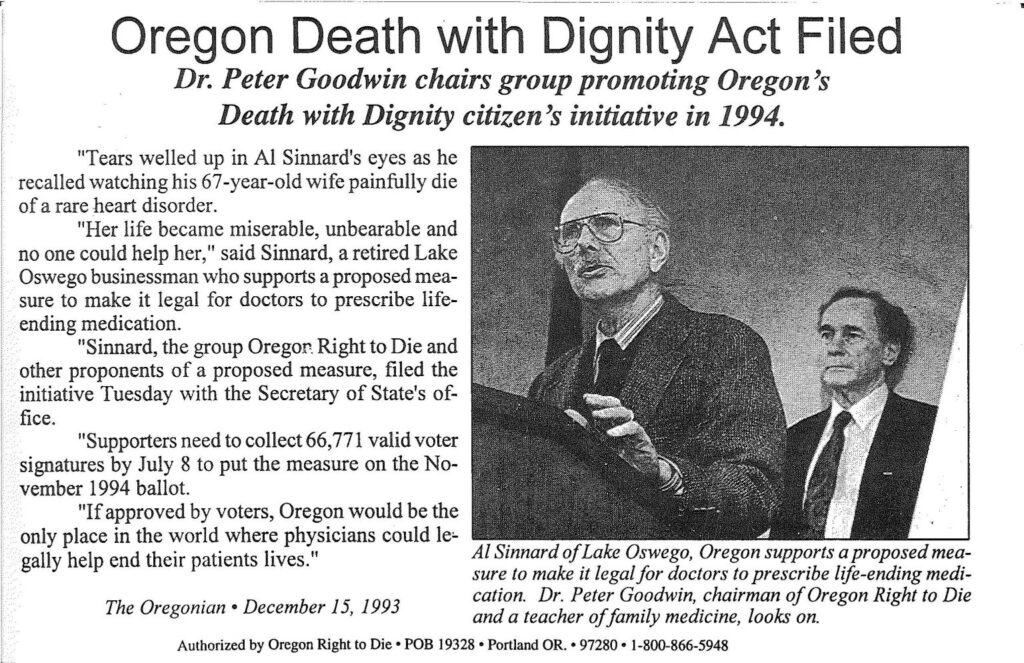

In 1993, we got together a powerful team that formed the Oregon Right to Die Political Action Committee.

Death with Dignity National Center co-founder Eli Stutsman, who also was part of the steering committee for the PAC, was the lead author of what would become Measure 16, the Oregon Death with Dignity Act.

The PAC team looked to the lessons of California and Washington, where we lost, to develop its own campaign. Lesson 1: the groups leading the initiative process in those states raised a lot of money, but on the eve of the election they had no money left.

So the leaders of Oregon’s PAC decided they would spend nothing on the campaign until the last week before the election. When election week came up, the PAC poured all of its money into radio and TV advertising. That was one of the key factors [in the passage of Measure 16].

A Physician’s Influence

The other factor was Dr. Peter Goodwin, one of the PAC’s co-founders. He argued successfully in committee meetings as we put the law together that we had to [draft the legislation] so it fit within the health laws of Oregon.

He argued it should be the patient only that could [hasten their death]. If a patient’s doctors agreed the patient was dying and there was nothing else they could do, doctors should prescribe the requisite medication, but never inject it. The patient would be allowed to fill a prescription at a pharmacy, take it home, and use it whenever the patient chose to die.

Out-Argued

That argument won, but I voted against it! I thought there were cases where injection was necessary. People with throat cancer and so forth who can’t swallow. There are some cases [where it makes sense]. I was out-argued. In terms of politics, [Oregon Right to Die] turned out to be right, and I was wrong. We won because of their strategy.

“A Good First Step”

I still don’t think the Oregon law is perfect. Countries like the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg have “my” kind of law: one that allows the patient to request either drugs or lethal injection. I think that’s the way to do it, and it seems to work out for [those countries]. But Oregon’s law is a good first step.

Information Agent

Humphry has served as a crucial conduit of information about the worldwide movement to legalize medical aid in dying. From 1994 until May 2020, Humphry moderated a listserv for the World Federation of Right to Die Societies, a widely distributed daily email news roundup featuring stories about efforts to pass legislation in the U.S., implementation of such laws in Canada, Switzerland, and other counties, and other noteworthy developments in a diverse global movement.

People still call me or email me with questions about how to die. They contact me via telephone and email, every day of the week. My listserv reaches people around the world.

I’m an information agent. I leave the rest to organizations [like Death with Dignity].

I’ve never lost sight of what I really wanted: legislation. When there’s adequate legislation across America, I will stop publishing Final Exit because it won’t be needed.