Lindzy B. is a store supervisor in York, Pennsylvania.

My father was diagnosed with ALS in 2009. I was in 8th grade at the time; my sister was 20. The whole week after his diagnosis we cried as we tried to absorb the information and figure out our next steps. We did a lot of research, trying to understand what ALS was and how we could best support my dad through the course of his illness.

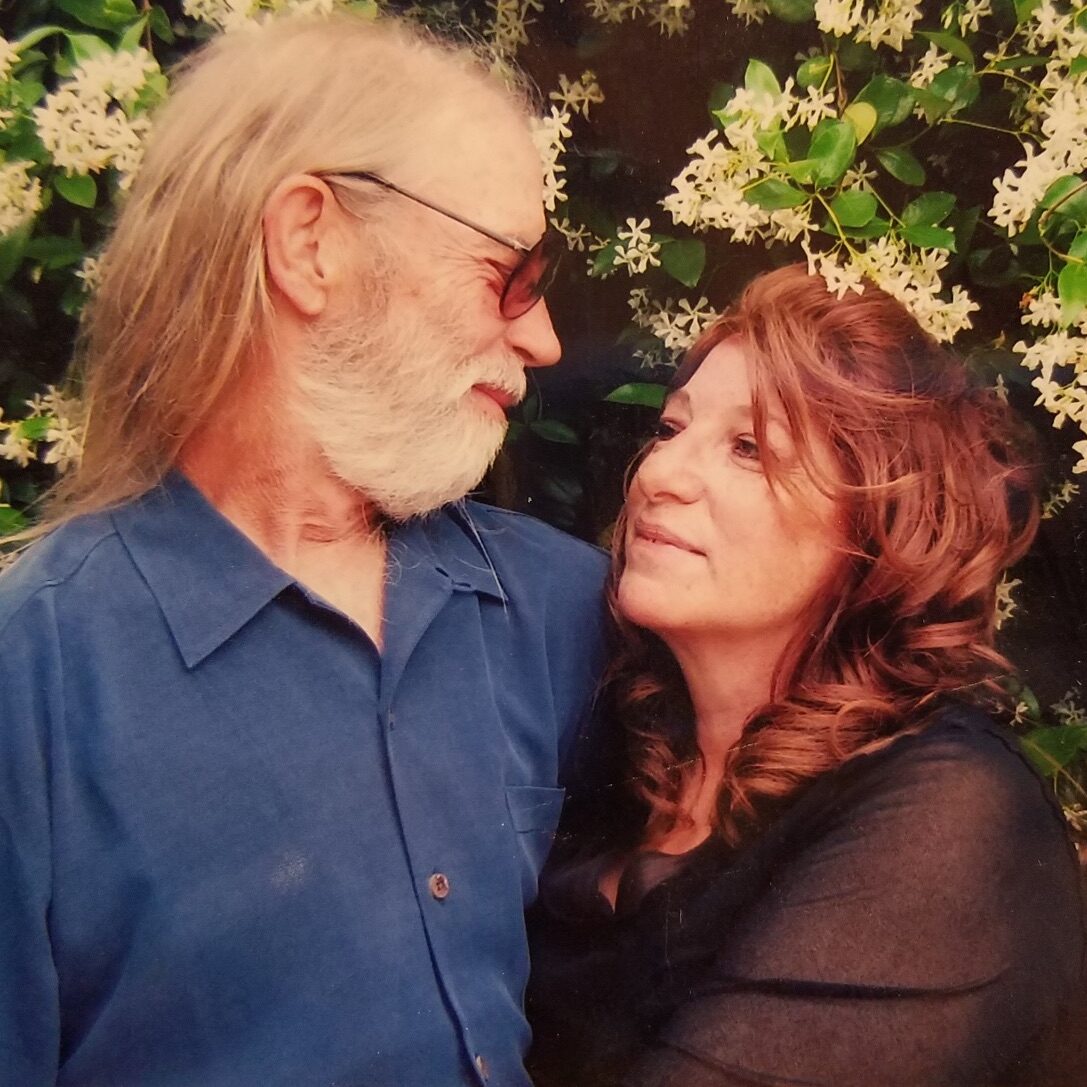

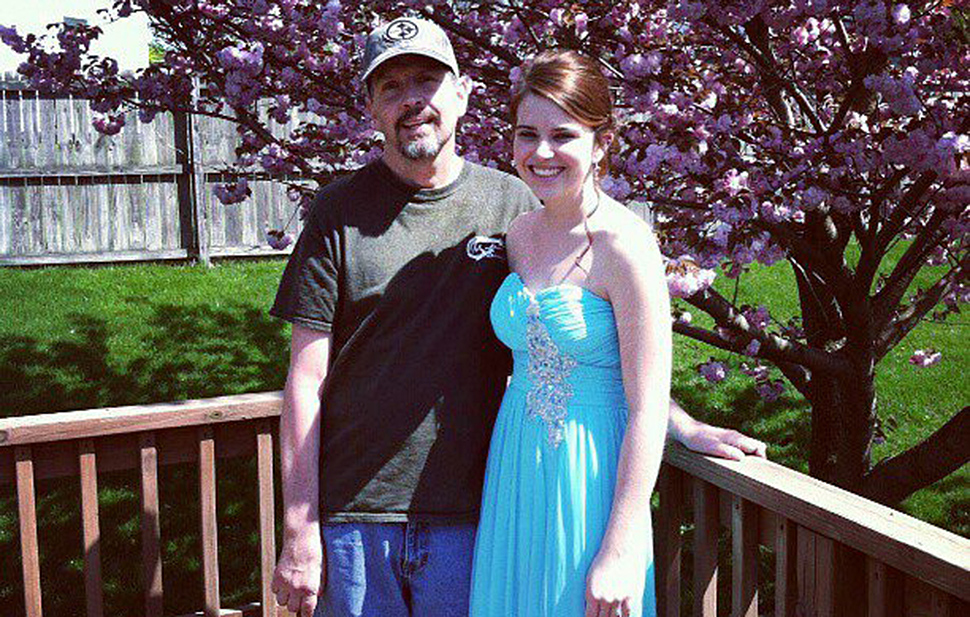

He was such a great dad. He was very loving, goofy, and happy all the time. Everyone who met my dad loved him. Even when he was diagnosed, he was as positive as he could be. He never complained or said, ‘why me.’ He just kept smiling.

He continued to work for three years after he was diagnosed. He worked at a lettering business, making signs for businesses and designs for T-shirts and car decals. His arms and hands were his tools, but unfortunately those were the first to go. He would come home very frustrated because he couldn’t hold a pen anymore. But he was stubborn, and worked until he physically could not do it anymore. I had to drive him to and from work because he couldn’t drive himself. We had to tell him, “You just can’t keep doing this to yourself. You have to stop.”

At first, my family and I took care of my dad in shifts. My mom would do the night shift after an 8-hour work day; my mom’s parents would come and help out a few days a week. In the end, it was too much. We had to look into 24/7 home care because he was literally unable to do anything for himself.

Some of the things I saw and had to do with my dad I wouldn’t wish on anyone. Near the end, we were in and out of the hospital with him all the time. The only time he got out was to go to his appointments. Getting him into the car alone was a 30-minute task. He was as positive as he could be, but near the end he was miserable and felt so alone and depressed. He almost completely lost his voice—the only thing he had left. He didn’t want us seeing him the way he was near the end.

Those years were incredibly stressful for my family. We all had a lot going on in our lives: work, school, relationships. It was so painful, especially towards the end. It helped bring us closer together, but it was a lot to handle.

My dad passed away on March 23, 2016, in the middle of my spring semester of college. My mom really lost it. We’d have friends try to get her up and moving, which was hard to do. At first, my way of dealing with his passing was to not deal with it. I felt like I needed to be the strong one; I needed to be there for my mom. But I grieved in private. When no one was around, I’d break down.

Now I’m taking time away from college to deal with my grief. I tried to push through my fall semester last year, but I was depressed and couldn’t focus on my work. All I could think about was my dad. Seeing what he went through was so traumatic. I decided I needed to take time off and return when I was capable of doing as well as I know I can in my classes, instead of just trying to struggle through.

I first learned about Death with Dignity while working on a psychology paper. I found an article on the Death with Dignity National Center website and started reading more about it. If my father had been given the opportunity to end his suffering, he would have taken it. It would have spared him so much pain, and would have taken away so much of the pain we went through as a family. My dad would have still had his dignity, and we would all have been able to say goodbye to him while he was still himself. We would have had closure.

To me, death with dignity means hope. It means even though you have a diagnosis that will end your life you can take back some of that control and decide when you want to die.

I live in Pennsylvania, where currently there is no death with dignity law. Everyone should be able to have the ability to use death with dignity, even if they don’t want to use it in the end. It means that they’re able to pass on their own terms, when they’re ready.

My sister and I made Facebook cover photos that said, “I support death with dignity.” One woman commented that people who support those laws are going to hell. It’s so much different when you have to live with someone who has a terminal illness. Many people think it’s just people killing themselves, when it’s not that at all. It’s people not having to suffer. If more people did research and saw all the good that death with dignity could do for people, they would change their opinions.

To me, death with dignity means hope. It means even though you have a diagnosis that will end your life you can take back some of that control and decide when you want to die. I believe all 50 states should have a law allowing death with dignity and stop allowing people to suffer.